Krystal Abrams, Social Media and Pollinator Projects Manager

Native American Tribes and First Nations are most at-risk of suffering the devastating effects of climate change. Climate change is no longer a distant threat, but a dangerous force that places our native communities and resources at immediate risk. As with so many threats, indigenous peoples have been at the front lines of the devastation caused by climate change, forced to fight to protect their land, homes, and culture. Across the nation, tribes are rallying together to fight against climate change. Although this issue impacts everyone in the world, it has an even greater impact on indigenous people and their lands.

What makes a community more vulnerable to climate change? Some factors include proximity to rivers and coastal floodplains, residing in areas prone to extreme weather conditions, and economies that are heavily dependent on climate (like agriculture, fishing, and winter sports). Many Native communities in the Pacific Northwest fit into at least one of these categories and many are already implementing climate action plans.

The ATNI Climate Change Summit

This summer I visited Kalispel land in Spokane, Washington to attend the Climate Change Summit with the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians and allies. This summit brought together leaders from Tribes and First Nations throughout the Pacific Northwest and North America to discuss tribal efforts to address climate change. The summit focused on tribal climate resilience, protecting and applying Traditional Knowledge in climate change initiatives, and implementing a unified tribal climate change policy agenda.

What are tribes doing to prepare?

Overall, tribes were focused on immediate action, as many nations are already feeling the harsh impacts of climate change, right here in the Pacific Northwest.

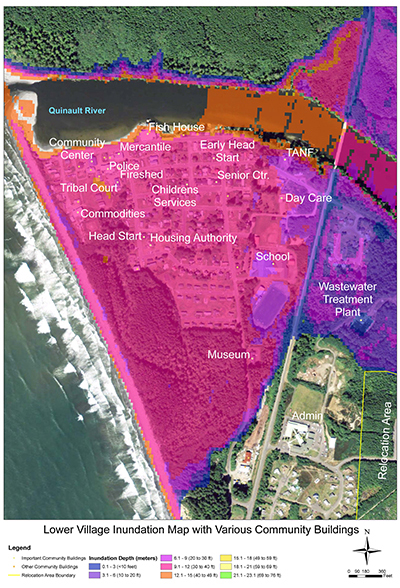

Inundation map shows where the Village of Taholah is under threat from tsunamis, storm surges and riverine flooding. A vast majority of the village is at risk of being under 20-30 feet of water with little to no notice.

A woman from the Quinault tribe on the Washington Coast mentioned that her tribe was considering a relocation plan. If adopted, this would involve moving nearly the entire village further inland. That’s because of sea level rises, brought on by climate change, that have swallowed a chunk of the coast. The Quinault, whose ancestors lived in their fishing village since time immemorial, are now faced with the prospect of uprooting their families and moving to higher ground.

The tribes in attendance also identified another crucial way to prepare for climate change: respecting and protecting traditional knowledge and incorporating it into future conversations to help shape future adaptations. Attendees all felt it was a priority to protect traditional knowledge within climate change initiatives, and rightfully so. After all, without the knowledge of our past, how can we hope to create a vibrant and equitable future?

The concept of Decolonizing Science was a hot topic addressed during presentations and discussions. This subject can be difficult to understand, after all, what does it actually mean to “decolonize” science? In other words, how has science been used as an instrument of colonization? As a science major and an indigenous woman myself, I can say with certainty that the current system that excludes indigenous knowledge in the scientific process is a problem. However, I see the concept of indigenizing the scientific method as a way to empower people to think about the natural world in a different way.

To decolonize does not displace objective data collection or methodology and has the benefit of improving science by incorporating ways that indigenous people think about and understand the physical world. It’s important to remember that our ancestors have cultivated and managed biological diversity for thousands of years. The extractive, euro-introduced economy is still very new in this place and is becoming a more toxic problem every year.

Perhaps the problems the world faces today would be better addressed if we considered those other solutions or ways of thinking instead of belittling them. One panelist, Clarita Lefthand-Begay, even took it a step further and described her research geared toward Indigenizing the Scientific Method, which essentially proposed ways to make the scientific method more native-friendly. She shared her expertise in both indigenous research methods and western scientific research methods, as well as her perspective about how to draw those two ways of knowing about the world closer together. There are many different ways to think about science and they can’t all be learned from a textbook.

Next steps

We can, in turn, learn how to build more resilient communities by taking the lead from our tribes who are refusing to turn a blind eye to these issues, and instead are rising up to make a difference. Our tribes are tackling climate change through many different avenues, such as taking a leadership role in other climate-smart trends, like renewable energy and sustainable housing development. Our tribes are stepping up to take action. Climate change is harming our tribal communities and threatening our culture. Not only is it unfair to discount the hardships our tribes endure--through no fault of their own--but it’s also unwise to ignore all the great work these communities have done to strengthen climate resiliency on tribal lands.

Since the arrival of European immigrants over 500 years ago, mainstream society has excluded the voices of indigenous peoples. This is especially true for conversations around climate change because everyone will be impacted, regardless of race, class, and privilege. If we want all of our communities to thrive in a rapidly changing and unpredictable climate, we must end this euro-introduced mentality of exclusion and denigration. Our society must invite tribal members to share their knowledge and perspectives in every task force and at every level of decision-making.

Krystal Abrams,

Social Media and Pollinator Projects Manager