PFAS Chemicals

PFAS chemicals are a class of chemicals that appear to have infiltrated every corner of our modern world. PFAS’ human-made chemicals are in our blood, clothes, and cosmetics. They are in air, water, soil, sediments, and in rain.

In 20051 and 20092, laboratory tests found PFAS chemicals in the umbilical cord samples from 20 babies born in the U.S. These tests exposed the shocking truth that American babies are born pre-polluted with PFAS, which can pass from mothers to fetuses through the umbilical cord. Most recently, in 2016 a Canadian study found PFAs chemicals in more than 90 percent of the nearly 2,000 cord blood samples collected from pregnant women.3

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly all Americans have PFAS in their blood.4

History and Definitions

PFAS

PFAS stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, it’s an umbrella term for a family of thousands of chemicals – about 12,000 at last count – that are prized for their indestructible, and non-stick properties.5 They are used in a huge range of consumer products, including waterproof clothing, furniture, cookware, electronics, food packaging and firefighting foams and are in a wide array of industrial processes.6

PFAS’ pervasive presence in the environment is a high concern for human health issues as they are absorbed faster in human cells than they can be excreted, thus they inevitably build up, bio magnify,7 and bioaccumulate8 up the food chain, thus effecting human health.

Finally, PFAS are designed so that they won’t break down in the environment for tens of thousands of years, earning them the true, but terrifying title, “forever chemicals”.

Why are PFAS a concern?

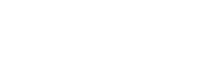

PFAS either are, or degrade to, persistent chemicals that accumulate in humans, animals and the environment. This adds to the total burden of chemicals to which people are exposed (Evans et al., 2016) and increases the risk of health impacts. Of the relatively few well-studied PFAS, most are considered moderately to highly toxic, particularly for children’s development. Figure 1 summarizes current knowledge of the health impacts of PFAS.

Source: National Toxicology Program. 2016. Immunotoxicity associated with exposure to perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) or perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS). US Department of Health and Human Services, Research Triangle Park, NC. [cited 2020 July 13]. Available from:

https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/ohat/pfoa_pfos/pfoa_pfosmonograph_508.pdf

What are the main routes of human exposure to PFAS?

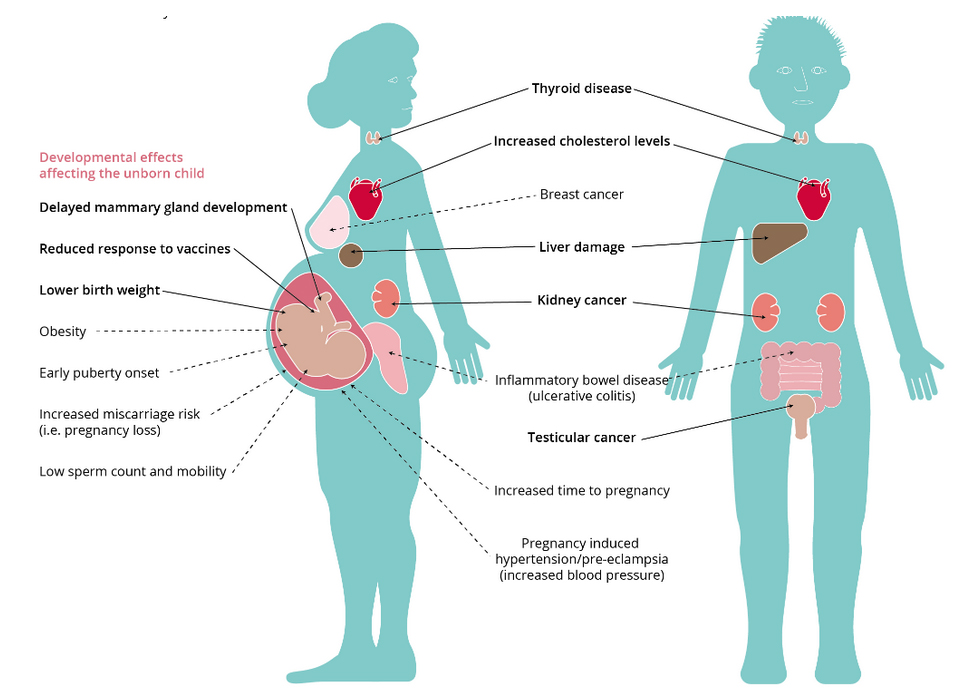

The main exposure pathways for human and environmental exposures are shown in Figure 2. For the general population, PFAS sources include drinking water, food, consumer products and dust (EFSA, 2018). In food, fish species at the top of the food chain and shellfish are significant sources of PFAS exposure. Livestock raised on contaminated land can accumulate PFAS in their meat, milk and eggs (Ingelido et al., 2018; Numata et al., 2014). Direct exposure may also come via skin creams and cosmetics (Danish EPA, 2018; Schultes et al., 2018) or via air from sprays and dust from PFAS-coated textiles. There is little knowledge on uptake via skin and the lungs, which can be severely affected by PFAS (Nørgaard et al., 2010; Sørli et al., 2020). Consumer exposure may also occur via other routes such as via floor, wood, stone, and car polishing and cleaning products. Groups that may be exposed to high concentrations of PFAS include workers and people eating or drinking water and foods contaminated via PFAS treated food contact materials (Susmann et al., 2019).

Source: Emerging chemical risks in Europe — ‘PFAS’ - European Environment Agency | Figure 2: Typical PFAS exposure pathways | https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/emerging-chemical-risks-in-europe

What are the main sources of environmental PFAS pollution?

Production and use of PFAS have been the main sources of PFAS contamination over time (Wang et al., 2014a, 2014b; Hu et al., 2016) for instance from fluoropolymer production installations and from the use of PFAS-containing firefighting foams (Figure 1). Other sources include PFAS produced and applied to textiles and paper and painting/printing facilities (Danish EPA, 2014). Less is known about potential releases of PFAS from other uses such as oil extraction and mining (Kissa, 2001), and the production of medical devices, pharmaceuticals and pesticides (Krafft and Riess, 2015).

PFAS in consumer products, such as textiles, furniture, polishing and cleaning agents and creams, may contaminate dust and air, while food contact materials can contaminate food (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2019; Danish EPA, 2018). Drugs and medical devices may be other sources.

Emissions to the environment occur via industrial waste water releases, as well as emissions to air from industrial production sites followed by deposition onto soil and water bodies. Industrial and urban waste water treatment plants are also a significant source of PFAS, via air, water and sludge (Hamid, et al., 2016; Eriksson et al., 2017).

Reuse of contaminated sewage sludge as fertilisers has led to PFAS pollution of soil (Ghisi et al., 2019) and water in Austria, Germany, Switzerland and the US (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2019). The recycling of PFAS containing materials such as food contact materials and the formation of volatile fluorinated gases during waste incineration (Danish EPA, 2019) are other possible sources of PFAS pollution.

What is Being Done About PFAS?

PFAS are currently not regulated in drinking water at the federal level, however the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has begun the process to regulate PFOS and PFOA in drinking water and it is very likely that federal maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) will be established for at least these two PFAS contaminants in the future.

In lieu of a federal drinking water regulation, several states have or are in the process of developing their own MCLs or health advisory levels.9

EPA

APRIL 2024 UPDATE

On April 10, 2024, EPA announced the final National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) for six PFAS. To inform the final rule, EPA evaluated over 120,000 comments submitted by the public on the rule proposal, as well as considered input received during multiple consultations and stakeholder engagement activities held both prior to and following the proposed rule. EPA expects that over many years the final rule will prevent PFAS exposure in drinking water for approximately 100 million people, prevent thousands of deaths, and reduce tens of thousands of serious PFAS-attributable illnesses.

Under "Summary," see the table of Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) allowed: https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas

NOTE: The EPA rules apply to drinking water. Beyond Toxics advocates for extendind standards to surface water.

Background

On February 1, 2024, the EPA announced the Biden Harris administration’s steps to protect communities from PFAS.10 EPA proposed two new rules that would better enable regulators to address PFAS under the nation’s hazardous waste law to protect families across the nation.11 The first proposed rule would modify the definition of hazardous waste as it applies to cleanups at permitted hazardous waste facilities.12 And the second would amend its RCRA13 regulations to add multiple PFAS compounds as hazardous constituents.14

Oregon

The Oregon Health Authority – Drinking Water Services (OHA-DWS) has established drinking water health advisory levels (HALs) for four PFAS compounds most found in humans. These health advisory levels for PFOS, PFOA, PFNA, and PFHxS are based on adverse developmental and immune effects and are set at levels meant to protect all persons, including sensitive populations, from both short and long-term exposures in drinking water.15

Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ)16 is working with landowners of several sites where PFAS have been found in one or more of the following media: groundwater, soil, surface water and stormwater. Contamination at these sites appears to be related to firefighting foam. Landowners are voluntarily assessing the contaminated sites with DEQ oversight and consultation as part of voluntary investigations of historical firefighting foam use and storage areas.17

DEQ’s Toxic Reduction and Safer Alternatives programs are also working to identify alternatives for PFAS in food packaging; coordinating with the state of Washington on PFAS-related efforts; collaborating with the Interstate Chemicals Clearinghouse and other states to assess firefighting foam alternatives; promoting awareness that individuals can purchase PFAS-free consumer products; and promoting PFAS-free materials in state purchasing contracts.18

According to Oregon.gov, the OHA conducted a 2013-2015 analysis of major public drinking water systems and found no detectable PFAS in Oregon’s drinking water systems.19 The OHA conducted another drinking water monitoring project in fall 2021 through 2023, at public water systems identified as at risk due to their proximity to a known or suspected PFAS use of contamination site.20

SPRING 2024 UPDATE

Oregon was part of a massive PFAS class action lawsuit vs. 3M corporation re: PFAS contamination in drinking water systems. The suit recently settled for $10.3 Billion. Distribution of the available funds is yet to be determined.

Beyond Toxics

Extensive monitoring of surface water sources for PFAS has not yet occurred in Oregon. Monitoring is the only way to know for sure whether water quality in Oregon's rivers have concerning concentrations of forever chemicals. A targeted PFAS sampling effort will determine whether people and wildlife are being exposed to potentially harmful PFAS chemicals in their drinking and surface waters. Beyond Toxics strongly recommends that the Oregon DEQ adopt timely and mandatory monitoring of PFAS in Oregon’s water ways to understand the potential risks of rising levels of these hazardous chemicals in the environment.

We are also concerned about understanding how children may be exposed to PFAS in everyday products. In partnership with Oregon Environmental Council (OEC), Beyond Toxics received a grant from the OSU's PNW Center for Translational Environmental Health Research to conduct Oregon-based research to detect the presence of PFAS in common consumer items, like artificial turf, cosmetics and consumer goods. The focus of the research will be on products typically used by young people. We hope the results will help inform how PFAS chemicals may transfer from products to our bodies through skin contact.

Resources

Proposed PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation - EPA

Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

ALSO:

See Chemicals that were once common and are now banned in the U.S. (information provided by Stuart Greenleaf)

Back to Waste Management Projects